El inglés en Irlanda

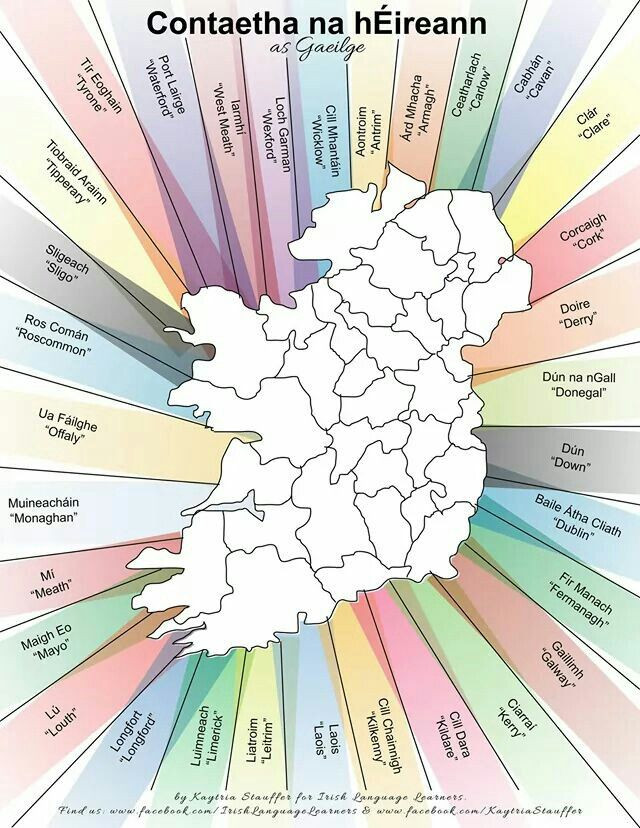

Irish English is a national variety of English. It has a special position as the oldest overseas variety of the language. The endemic language of Ireland, Irish (or Gaelic - not to be confused with Scottish Gaelic), has a more symbolic value now - it is spoken mostly in the West and encouraged by policies that make it the first language to appear in public signs or in European texts for example.

“In policy and ideological debates, Irish English takes second place to Irish since Irish claims symbolic value and a link to perceptions of cultural authenticity” (Kallen 2013:45)

1 The Irish language as the national language is the first official language.

2 The English language is recognised as a second official language.

(Article 8 of Bunreacht na hÉireann - Constitution of Ireland)

History of English in Ireland: a story of coexistence, contact and shift

Irish-English is a result of the contact between English from Great-Britain, French (both firstly coexisted because of foreign settlements) and Irish. There has been successive shifts as one gets stronger than the others (while the influence of the latter remains)

Anglo Irish a loaded term, ideologically; language use by English speaking settlers in Ireland (earliest use 1626)

Hiberno-English (refers to Latin name for Ireland, Hibernia): more used by scholars, less used than Irish English

Irish English: Not so ‘sentimental’ as Hiberno-English, congruent with terms for other World Englishes (it follows the logic of 'local Englishes' like American English, Australian English...)

1. End of 12th century – arrival of the Anglo Normans from the Coast of West Wales

English became established in a band from Dublin to Waterford (mainly in the towns). Gaelicisation led to the low point of English at the end of the 16th century. English was getting stronger amongst spoken languages in Ireland even when Gaelig was the first language. Even at declining moments in English in favour of Irish, the new language was still used and influenced Irish (e.g. Kildare poems).

2. 17th Century to the present day the defeat of the Irish in the battle of Kinsale (1601)

First: settlers from Lowland Scotland in the North of Ireland

Later: plantations in the South

Irish started its stronger decay after the battle of Kinsale (1601). The general decline of Irish went along with an increasing emigration. Migration caused a direct shift: Irish people left Ireland exporting Irish English, whereas English people immigrated to Ireland.

The different phases of one or the other language's strengthening are due to transportation, coexistence, contacts and shifts.

Linguistic features of Irish English

The sounds of Irish English

“The phonology of Irish English” = an abstraction! (Hickey)

Well’s vowel chart: lexical sets based on a group of words, all of which have the same pronunciation for a certain sound in a given variety.

The grammar of Irish English

Factors affecting the development of Irish English grammar:

Conservatism : retention of features of earlier ‘mainstream’ English

Dialect contact with other varieties of English

Contact influences from the Irish language: substratal influences

Universal features associated with second language acquisition (SLA ) in intense language shift conditions

Morphology

Second person plural subject pronoun: ye, yez , youse (vous-vosotros/as)

Second person plural complement pronoun: yeer (votre-vuestro/a)

Epistemic negative mustn’t : He mustn’t be at home now

Use of them as a demonstrative: Them things

Simple past done and seen: He done some work

Negation of auxiliaries: Amn’t I leaving soon anyway?

Syntax

Verb forms : I wonder why he done that.

Negative Concord: The corporation don’t give no loans.

Clefting : It’s to Glasgow he’s going.

For to infinitives for purposes: He went to Dublin for to buy a car

Til for in order to: Come here til I tell you

Use of definite article: He likes the life in Dublin

Perfectives:

Resultative perfective with the word object + Past Participle: She has the housework done. (intentional action)

Habitual aspect (present):

does be (often reduced on the east coast to d əˡ bi ]): he does be reading books.

by inflectional s: they calls that part down there ’High Street‘.

bees (exclusively northern): The kids bees up late at night.

Immediate perfective with the structure after + V ing (+ O): She is after spilling the milk. (hot news)

Influence of the Irish language on Irish English syntax:

To be after V+ing (Focus on immediate outcome/ recency) - A calque of an Irish construction:

Tá mé tar éis an teach a ghlanadh

V + S + Prep .. +N ( O) +part V

(Is - I after the house cleaning)

The vocabulary of Irish English

Chisler: child

Class: cool

Cog: cheat

Culchie: denotes country (social definition: all but Dublin)

Mitch: play truant (not to go to school when you should)

Craic: fun, funny < Gas: very funny

Grand: ok, nice

Pint: scoop (for a drink)

Smashing: great

Tackies: running shoes (mainly in C. Limerick)

The finest: the best

What's the craic: how are you, how are things, what's going on

Yoke: thing

Merger of items: bring and take, rent and let, borrow and lend, learn and teach

In IrishCentral.com

Acting the Maggot: Acting in a lighthearted, non-serious manner

As in: Would you ever stop acting the maggot and peel those spuds, like?

Aul Wan: Your own, or anyone else's, mother

As in: Is that your aul wan waiting for you at the school gate?

Bettys: Women

As in: Did you ever see so many Betty's in the one place, like? We're laughing.

Beak: Mouth

As in: If he doesn't stop singing "Ice Ice Baby," soon I'm going to hit him a clatter on the beak.

Bogger: A rural person (offensive)

As in: There must be a new tractor show. The town's overrun with boggers, like.

Chancer: A person who continually pushes their luck

As in: That government minister's a right fecking chancer.

Clatter: To punch

As in: I'll give you such a clatter on the gob you'll need a team of nurses, like.

Cute Hoor: A highly manipulative person

As in: He's some cute hoor that lad, isn't he? Started off in the mail room and now he's running the company.

Dose: An individual of little personal charm

As in: Jaysus, your cousin Michael's an awful dose. Where did you find him?

Eejit: Idiot

As in: You're an awful fecking eject, do you know that?

Feck: Hiberno corruption of the Anglo Saxonism

As in: Feck me, lads. Get to feck. Who's that big fecker?

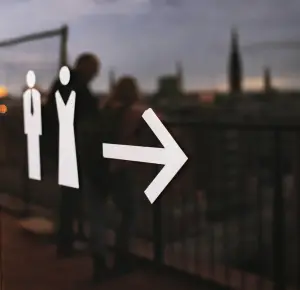

Jacks: Restroom

As in: Hi, where's the jacks? I'm busting.

Mingin': Offensive, displeasing to the eye or nose

As in: You couldn't eat that there fish, Majella, it's mingin'

Plastered: Intoxicated

As in: Your man over there's plastered, don't let him drive anyone home.

Savage: Awful

As in: Your man got up and sang a wee song then and it was savage altogether.

Scald: Tea

As in: Any chance of a cup of scald there missus?

Sky Pilot: Absurdist catch-all insult

As in: Away to hell you feckin' sky pilot!

Tool: Dolt, foolish person

As in: Your brother Aidan is a complete feckin' tool.

Irish words in English

Slán: Goodbye

Banshee (fairy woman) comes from “bean” (woman) and “sí ” (fairy)

Keening (wailing) comes from “caoine” (wail)

Brogue (wooden shoe). The Irish were said to speak with a shoe in their mouth, hence, their “Irish Brogue.”

Shenanigan comes from “sionnachuighim ” (I play tricks)

Smithereens comes from “smideirin ” (a small fragment)

Shanty comes from “sean tigh ” (old house)

Describing contemporary Irish English

The database of spoken Irish English is made of 2 main corpora: LCIE (Limerick Corpus of Irish English) and ICE-Ireland (International Corpus of English - Ireland, larger-scale project)

Analysing those corpora, in particular the most frequent terms used, gives a more accurate understanding of contemporary Irish English.

The pragmatics of Irish English

Pragmatics is the study of contextual language use.

Pragmatic features of Irish English:

'Hi how are you' can be a greeting or a genuine question

First names are more used than last names in Irish culture

Use of English words with a specific Irish meaning

Indirectness: avoiding yes or no

Understatements: negative constructions instead of direct requests (“not not bad”, “you wouldn't have”...)

Hedging (hedges: maybe, kind of, sort of, just, old... used in combination with would), to lessen the force of an utterance, and syntactic downtoners (would, I'd say, we could...), to reduce the force or the emotional impact of an utterance, which are more used by Irish English speakers than British English and American English speakers. It can be used for positive face (need to belong, to be liked, sense of solidarity) and negative face (respecting somebody's need for independence and own decision making)

Pragmatic markers: like (to avoid directness, a feature of a particular social group), sure, surely, of course, now, so, well, but, you know, you see... They can change a message (social aspect of the interaction: creates a deeper social connection, or familiarity)

Small talk

Expressions of listenership (interrupting, wanting to get a turn in): a positive thing in Ireland

Reoffers and ritual refusals

Use of vocatives

Pragmatic features can be a sign of identity; they set people apart from a social point of view.

Irish Englishes - many sub-varieties

Today’s Irish English is actually plural: there are variations across the territory with changes in terminology and most of all in pronunciation, from a county to another and even on a smaller scale from a city to another.

The Irish Travellers’ English

The Irish Travellers are an indigenous community, symbolically (not officially recognised) ethnic minority community. Some of them want to be recognised officially as such while others don't want a special treatment and don't accept this categorisation. They’re historically nomads and there is a central importance of family in their culture. The Irish Traveller community is often confronted, in public places where they have interactions with people from the settled community, or 'mainstream' community, to prejudiced discourses and discriminative behaviours.

The population is around 29,6 in Rol (<1% of overall population). It’s a number difficult to calculate (more or less reliable figure): a lot of them don't mention that they're from the travellers community on the paper.

Find out more about the Irish Travellers' community in this documentary series: RTE2: John Connors: The Travellers

The English spoken by the Irish travellers is a local variety, an overarching social variety, quite cohesive.

Archaic Irish English features

Shelta substrate?

Long monophthongal quality of FACE, GOAT, FLEECE

Mid-central realisation of KIT, TRAP, STRUT and unstressed vowel towards /ə/ or /i/

approximation of certain KIT words towards STRUT in an [ɨ]/[ʉ] realisation: wrist [wrʉst], mirror [ˈmʉrə].

DRESS often raised to [e̝] or to KIT [ɪ], e.g. in den, Ben (also in IE)

Words with an onset <u> often aspirated, e.g. us [hʊs], under [hɔ̈ndə˞].

Words ending in -OW also commonly have a [ə], and can even be raised to an [ɪ]: follow [ˈfɒlɪ], which can be lengthened: window [wɪndiː].

Reduction and elimination of some unstressed syllables

-ING suffix is mostly reduced to /-ɪn/ or /-ən/

schwa absorption common for words ending in dentals: putting [ˈpʊtn], sitting [ˈsɪtn].

Unstressed prefixes of multisyllabic verbs often not audible: remember [ˈmembə], which gives a peculiar rhythm

Lexicon and pragmatics

Many Traveller English lexical features: childer, teach/learn, baba, yoke, holy show, lush, lurk, old-fashioned;

Religious expressions;

Infrequent use of hedging => "assuredness of their position" (Clancy 2011);

You know vs I think => "strong sense of community",

"may have a direct influence on their continuing marginalisation in modern-day Ireland” (Clancy 2011).

References

Clancy, Bryan (2022) ‘Language and Irish Travellers’, The Oxford handbook of Irish English, Oxford University Press. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/362253159_Language_and_Irish_Travellers

Hickey, Raymond (2004) A Sound Atlas of Irish English, Berlin/NewYork: Mouton de Gruyter, December 2004. http://www.raymondhickey.com/IERC_Sound_Atlas_(book).htm

Kallen, Jeffrey L. (2013) Irish English Volume 2: The Republic of Ireland (Dialects of English 9) Berlin De Gruyter xiv

Markku, Filppula (1995) The Grammar of Irish English Languages of Ireland (concise introduction page on Ireland.com): https://www.ireland.com/en-us/help-and-advice/practical-information/languages-of-ireland/

El rincón de lectura

Para saber más acerca de las lenguas y otros temas vinculados

Un poco de lectura ligera sobre temas lingüísticos, literarios o sociales, ¡venga a echarles un vistazo!

Teorías y reflexiones sobre la traducción

Your perfect tech rider

Sociolingüística: conceptos claves

Language accessibility in live performances

Aprender una nueva lengua

Oportunidades de vivo para artistas emergentes

Fracasos de traducción

Subtitling: use(s) and norms

La localización

Tablón de ofertas laborales en la industria musical

Youth Language

Onomatopeyas a través del mundo

Lenguaje y género

La manipulación de las palabras y realidades en la política

El lenguaje tabú

Language attrition

Cuando la comedia se burla de la interpretación

The meme corner - La música

The meme corner - Ser un(a) traductor(a) / intérprete

The meme corner - La lingüística

The meme corner - La traducción

The meme corner - La comida en el mundo