Sociolingüística: conceptos claves

Sociolinguistics is the study of variation of language in use: we use different words or grammatical forms depending on context

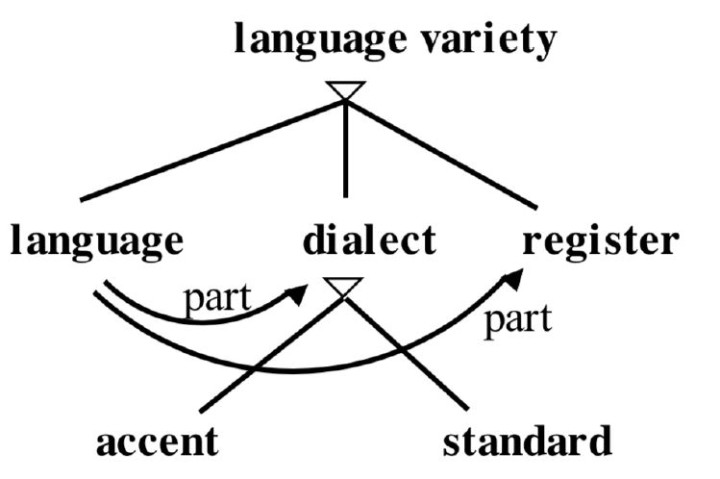

Language varieties

Regional variation

Dialect

A dialect is a sub variety based on social groups, e.g. geography, social class.

Dialects are mutually comprehensible variants of the same language that systematically differ in semantics (meaning of words), phonology or syntax. All equally rule based and logical, none is linguistically superior

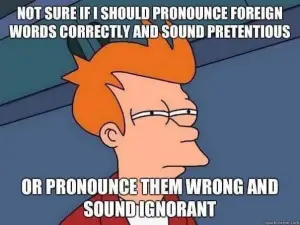

Certain dialects are more socially valued (due to the power and prestige of their speakers): a standard dialect/register is a sub variety with high social status. A dialect is valued, a standard is shared (for non-speakers). All have social value in certain settings, they value the speaker and his/her dialect while promoting access to standard English.

Language vs. dialect

We can’t define these based on mutual intelligibility or grammatical similarity. For example, Spanish and Italian are mutually intelligible, but not dialects of one language.

We can define them socio-culturally. “A language is a dialect with an Army and a Navy”

Dialect Geography

Dialectologists traditionally recorded the words and pronunciations of elderly speakers in remote villages. They showed their findings on maps, with a different map for each feature

They drew lines separating different areas of use: isoglosses.

More about the varieties of English here: http://www.raymondhickey.com/index_(SVE).html

Idiolect

An idiolect is every person’s own way of speaking.

Every person has their own way of speaking that differentiates their speech from others in the same community. The rules and principles that underlay that way of speaking constitute that person’s mental grammar. The output of an individual’s unique ‘grammar’ is called an idiolect.

Accent

An accent is a way of pronouncing a dialect e.g. RP (received pronunciation)

Social variation

A sociolect is a language variety that is associated with a specific social group (Collins dictionary)

A slang is an in group way of speaking with a strong in group solidarity function

Functional variation

A register is a sub variety based on social situations, e.g. chat, essay, prayer

Spatio-temporal evolutions of language

Diachronic Language Variation

All languages change over time. A language that stops changing begins to die. Living languages are in a continuous process of change and adaptation to new communicative needs.

Pragmatics

Pragmatics is the study of contextual language use.

It corresponds to the study of intended speaker meaning, because much more gets communicated than what is said. It is important to study pragmatics to understand the meaning of the language according to the context, otherwise there could be misinterpretations, miscommunication, that can lead to the formation of certain attitudes or stereotypes.

Pragmatic features: politeness, directness and indirectness, speech acts (wait or talk directly, the flow or interruptions of talk according to social expectations), denotation and connotation, Small talk, Slang, non-verbal communication (79% of the communication), prosody (related to voice).

Pragmatic features can be a sign of identity; they set people apart from a social point of view.

An interesting video presentation: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VKbp4hEHV-s

Hedging

Brian Clancy describes hedging as a “politeness strategy”. He states that “hedges function to down-tone the illocutionary force of an utterance allowing the speaker to weaken his/her commitment to its propositional content (see Brown and Levinson, 1987)”.

Negative politeness according to Amador-Moreno's definition: “using language to minimise the imposition on the listener”.

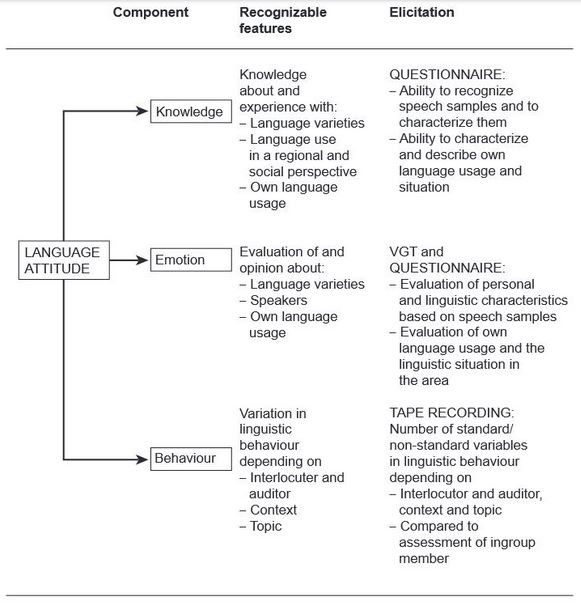

Language attitude

Language attitude is a “mental disposition towards something”, it acts as a bridge between opinion and behaviour (Obiols 2002); or “any affective, cognitive or behavioural index of evaluative reactions toward different language varieties or speakers” (Ryan et al. 1982:7)

Language attitudes are the feelings people have about their own and other people’s language varieties. There is no intrinsic reason to language attitude, no intrinsic value to an accent.

Attitudes about language are learned, not inherent . And they aren’t really “logical” or “natural”. There is no such thing as an objectively beautiful/stupid/easy to understand/etc. language or dialect, it’s all socially constructed.

The way we speak generates judgement (social reception of language). Be cautious about accepting anything someone says is “logical” or “common sense”.

Because language is flexible and somewhat controllable, criticising someone’s language is a more socially acceptable way of attacking someone than something that seems like bald faced racism/sexism/homophobia/etc.

Stereotypes

British: sophisticated / Irish: less sophisticated, more “rural” / Scottish: friendly

"Women talk too much"

"Children can’t speak or write properly any more"

"In the Appalachians they speak like Shakespeare"

"Black children are verbally deprived"

"They speak really bad English down south and in New York city"

"Everyone has an accent except me"

To Holmes (2008, p. 405), “attitudes to language reflect attitudes to the users and the uses of language”. “There is nothing intrinsically beautiful or correct about any particular sound.”

“[People] develop attitudes towards languages which reflect their views about those who speak the languages, and the contexts and functions with which they are associated.” (Holmes, 2013, pp. 409-410)

Attitudes may influence how teachers deal with pupils and they may affect second language learning.

Examples of strong views towards languages: (Holmes, 2013, pp. 410-411)

Language riots in Belgium and India

Getting rid of English road signs in Wales

Change in attitudes towards English and French in Quebec

Long delay in developing a script for written Somali because of competing prestige forms (Roman vs. Arabic alphabets)

Influencing factors of language attitudes

According to Reagan (2002: 47f.), and from an American point of view, the fundamental factors which determine language attitudes are the following:

the size of the language’s speaker community;

the geographic spread of the language (including its use as a second language, or lingua franca);

whether the language constitutes a heritage language in the local American setting;

whether the language is a language of wider communication;

whether the language has an established and recognised literary/written tradition; and

whether the language is a “living” or “dead” language.

Methodology

1. Societal treatment

Observing use in public domain

Examining government documents about status

Educational document

Employment advertisements

Dialect representation in novels

Cartoons (societal stereotypes)

Newspapers, books

2. Direct measures

Ask direct questions about attitudes

Written questionnaires (possible large scope)

3. Indirect measures: the Matched guise technique (elicits overt attitudes)

The Matched-Guise Test is a sociolinguistic experiment technique in two or more guises.

This experiment was first introduced by Lambert in 1960s to determine attitudes

An example from Giles & Powesland

Case-study: An investigator who could speak both the Birmingham accent and RP spoke to two groups of 17-year-olds about psychology, using one accent with one group and the other accent with the other group.

Result: The investigator was rated higher in his RP in terms of competence, intelligence, and industriousness.

Overt and covert prestige

Overt prestige

Standard varieties have overt prestige. They’re rated high on scales of educational and occupational status, indexes high social status

Covert prestige

Covert prestige: informal, likeability towards a language, value not publicly recognised, but positive attitudes towards vernacular and non-standard varieties (often not admitted: It's not always admitted that we like using our own accent)

Debate over the need of Lingua France, and the value of small languages

“[…] while RP tends to be rated highly on the status dimension, as in Britain, local [New Zealand] accents generally score more highly on characteristics such as friendliness and sense of humour, and other dimensions which measure solidarity or social attractiveness.” (Holmes, 2013, p. 417)

Attitudes are complex they can contain positive and negative aspects.

A prestige variety is a dialect associated with mainstream social prestige for example a dialect that sounds “ or “.

A stigmatised variety is a dialect associated with negative features, from a mainstream social perspective e g ..“ uneducated”“lower class”.

A negative prestige variety is one that is associated with negative social value, but also carries a lot of prestige in certain social groups. Example: Male speakers of certain regional dialects are often considered “extra masculine” within their social group

This easily leads to discrimination.

Ratings of RP Speakers vs. Regional-Accent Speakers: more intelligent, industrious, self-confident, determined, persuasive, more communicative effectiveness, more social status, more general pleasantness, often taken more seriously

Prosodic and pragmatic differences

→ cultural categorisation at first encounter

→ misunderstandings

→ conflicts

→ negative stereotyping

Discrimination as an effect of negative language attitude

To Edwards (2011, p.112), 'the social power of perception creates its own reality, and varieties broadly viewed as inferior are, for all practical intents and purposes, inferior'.

Edwards (2011, p.110) rhetorically asks 'what external enemy would refrain from the argument that an inferior language [seen as such] must necessarily attach to an inferior community?' As the evaluation of language is associated with that of the speakers of that language, we can reflect upon the social resonance of such a phenomenon.

Roberts (1992: 89): “there is a linguistic dimension to discrimination that is rarely perceived as such”

Discrimination towards vernacular accents

“I have tried to show that the reasons people condemn vernacular forms are attitudinal, not linguistic. Children who use vernacular forms are not disadvantaged by inadequate language. They are disadvantaged by negative attitudes towards their speech— attitudes which derive from their lower social status and its associations in people's minds.” (Holmes, 2013, p. 420)

Language ideology

A language ideology always has a specific history. Ideologies tend to be consistent for a community

Language ideology can tell us why languages are important to us, personally, and how they should be used (Armstrong, 2011).

There has always been an assumption that language that is not the language of the state should remain at home and not be spoken in public spaces, universities...

Ideologies are constantly shifting:

Rise of English as a dominant, global language, to the detriment of minority languages.

Even among speakers, debates over the minority language they speak, whether it is a proper language or a dialect of the majority language, and sometimes whether it is an accent or a dialect.

Studying language ideology informs why people use a specific language and decide which language to teach their children.

Deciding to teach or not one's minority language to one's children has a lot to do with social assimilation.

Attitude might be more visible on a personal level, whereas language ideology has more a society level, a political side.

Language policy

Language policy is one mechanism for locating language within social structures. According to Spolsky, language is “language policy with the manager left out, what people think should be done.”

Language policy as the legacy of colonialism?

Language shift is the process of losing speakers of the aboriginal language in favour of the colonial language. The decolonised states have troubles now with the issue of national languages and actually spoken languages.

Policy can emerge from ideology: imposing a certain language in certain places or situations… Ideology can influence how policies are interpreted: we don't have to use the language but acknowledge that it is there.

Linguistic Exchange (Bourdieu)

Linguistic exchange – ‘a relation of communication between a sender and a receiver, based on enciphering and deciphering, and therefore on the implementation of a code … is also an economic exchange which is established within a particular symbolic relation of power between a producer, endowed with a certain linguistic capital, and a consumer (or a market), and which is capable of procuring a certain material or symbolic profit.’

‘In other words, utterances are not only (save in exceptional circumstances) signs to be understood and deciphered; they are also signs of wealth, intended to be evaluated and appreciated, and signs of authority, intended to be believed and obeyed. Quite apart from the literary (and especially poetic) uses of language, it is rare in everyday life for language to function as a pure instrument of communication’

Questioning Boudrieu’s ideas

Jeremy F. Lane questions Bourdieu’s idea that “only those agents occupying relatively privileged positions in society are considered qualified to articulate potentially universal truths.”

The example of an interview with a your student with mixed ethnic identity (French/North-African) shows how he dismisses the legitimacy, and even right, for anyone to discuss his concepts, especially if they’re less educated: “[Bourdieu] does not need to provide any such evidence since his dismissal of her point of view rests not on questioning the intrinsic merit or rationality of her words but rather on pointing to the social position she occupies, a position that is assumed to render those words, by definition, illegitimate.”

Bourdieu seems to “know” who is, on the contrary, able and authorised to discuss sociology: “From a supposedly realistic description of the structural inequalities inherent to any linguistic exchange, Bourdieu thus moves to making a series of prescriptions regarding precisely which individuals can, by dint of their socio-professional status, be considered capable of articulating ideas of potentially universal sociological validity.”

Linguistic Capital (Bourdieu)

Utterances are always ventured in a particular field or market, in which certain social expectations for speech and interaction exist.

Bourdieu introduced the concept of linguistic capital to describe the respect or authority enjoyed by a speaker in the context of this linguistic market. In a linguistic market, people use different types of styles with an anticipation of a certain profit or outcome. Our choice depends on the kinds of perceptions and attitudes that we expect will be held towards a particular style that we use.

Roberts (1992: 89): “there is a linguistic dimension to discrimination that is rarely perceived as such”

Style is “individual deviation from the linguistic norm”. It exists only because we are able to “make distinctions between different ways of saying, distinctive manners of speaking”.

“Style, whether it be a matter of poetry as compared with prose or of the diction of a particular (social, sexual or generational) class compared with that of another class, exists only in relation to agents endowed with schemes of perception and appreciation that enable them to constitute it as a set of systematic differences.”

Intimate discourse

Politeness norms are different (politeness is done in a different way) according to the social group / context in which the speaker is.

"The evidence of non-imposition politeness in present day English comes from situations and contexts that can be described as public…these forms are much less appropriate and much less frequent in private situations" (Jucker 2012, p.431).

References

Amador-Moreno, Carolina (2010) An Introduction to Irish English, London: Paperback.

Baker, Colin (1992) Attitudes and language, Clevedon (England): Multilingual Matters.

Brown, P., & Levinson, S. C. (1987). Politeness: Some universals in language usage. Cambridge University Press.

Clancy, Brian (2016) An overview of intimate discourse. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/345940478_An_overview_of_intimate_discourse

Clancy, Brian (2015) Investigating Intimate Discourse: Exploring the spoken interaction of families, couples and friends. Routledge. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283638345_Investigating_Intimate_Discourse_Exploring_the_spoken_interaction_of_families_couples_and_friends

Clancy, Brian (2011) 'Chapter 7 - Do you want to do it yourself like? Hedging in Irish Traveller and Settled Family Discourse' in Davies, B.L., MHaugh M. And Merrisen, A.J., eds., Situated Politeness, Continuum, 129-146, available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265329171_'Do_you_want_to_do_it_yourself_like'_Hedging_in_Irish_Traveller_and_Settled_Family_Discourse, accessed on Dec 1st 2019.

Cummings, L. (2005) Pragmatics: A multidisciplinary approach. Edinburgh, Scotland: Edinburgh University Press.

Edwards, John (2011) Challenges in the social life of language, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, available: https://www-dawsonera-com.proxy.lib.ul.ie/readonline/9780230302204, accessed on Dec 1st 2019.

Edwards, John. (1999) Refining Our Understanding of Language Attitudes. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 18(1), 101-110, available: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0261927X99018001007.

Giles, H., & Powesland, P. F. (1975) Speech style and social evaluation. Academic Press.

Holmes, Janet (2008) An introduction to sociolinguistics, Third edition. Harlow: Longman.

Jucker, Andreas H. (2020) Politeness in the History of English. From the Middle Ages to the Present Day. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Labov, W. (1972). Sociolinguistic patterns. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Ladegaard, Hans J. (2000) 'Language attitudes and sociolinguistic behaviour: Exploring attitude–behaviour relations in language', Journal of Sociolinguistics, 4(2), 214-233, available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/1467-9481.00112, accessed on Dec 1st 2019.

Roberts, R.W. (1992) Determinants of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure: An Application of Stakeholder Theory. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 17, 595-612. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(92)90015-K

El rincón de lectura

Para saber más acerca de las lenguas y otros temas vinculados

Un poco de lectura ligera sobre temas lingüísticos, literarios o sociales, ¡venga a echarles un vistazo!

Teorías y reflexiones sobre la traducción

Your perfect tech rider

Language accessibility in live performances

Aprender una nueva lengua

Oportunidades de vivo para artistas emergentes

Fracasos de traducción

Subtitling: use(s) and norms

La localización

Tablón de ofertas laborales en la industria musical

El inglés en Irlanda

Youth Language

Onomatopeyas a través del mundo

Lenguaje y género

La manipulación de las palabras y realidades en la política

El lenguaje tabú

Language attrition

Cuando la comedia se burla de la interpretación

The meme corner - La música

The meme corner - Ser un(a) traductor(a) / intérprete

The meme corner - La lingüística

The meme corner - La traducción

The meme corner - La comida en el mundo