Lenguaje y género

Gender is “something that is performed, or brought into being in the act of speaking” (Swann, 2010, p. 234). Sex is a biological distinction whereas gender is socially constructed.

The ideology of gender categories is typically enacted in linguistic practices; indeed, it is through language that the individual cultural understandings of gender categories are learned and the coordination of gender roles achieved (Foley 2001: 289)

All of these categories affect language:

Sex: a biological category e.g. male, female

Gender: a social identity e.g. masculine, feminine, gender fluid etc.

Sexuality: heterosexual, LGBTI

Theories of the language and gender relationship:

1. Language and culture: If a culture is misogynist the language will be too.

2. Language itself can determine gender relations

Gendered language attitudes

Language conveys attitudes, sexist attitudes, which can stereotype people according to their gender. Language expresses negative and positive stereotypes about men and women.

Nearly always negative stereotypes of women e.g. dog v’s bitch

“Gender differentiation in language, then arises because…language, as a social phenomenon, is closely related to social attitudes. Men and women are socially different in that society lays down different social roles for them and expects different behaviour patterns from them. Language simply reflects this social fact.” (Trudgill 2000, p. 79)

“If the social roles of men and women change, moreover, as they seem to be doing currently in many societies, then it is likely that gender differences in language will change or diminish also….” (Trudgill 2000, pp. 79 80)

Sexism in language

It is the tendency to speak of people as cultural stereotypes of their gender.

Language is one of the tools used to distinguish between male and female in linguistic and sociolinguistic terms. The world mainly holds patriarchal societies, except for some communities like in Brazil that are matriarchal (female point of view favoured). Language reflects the (social) power that men have historically held in many areas of life, by treating words to refer to women as marked, while unmarked words are those that refer first to men and also to both men and women.

Language conveys attitudes, sexist attitudes, which can stereotype people according to their gender. There are always more negative terms for women than for men in stereotypes. Most societies are male-dominant, male-gazed, so the ideas conveyed are also favouring men.

Sexist language: female equivalents are often unequal e.g. mistress/master

Sexism in English

Like many other languages, English reflects the male orientation in society, the power that men have historically held in many areas of life.

Assertive, charismatic, articulate are associated with men

Feisty, chatty, fierce, bossy, assertive are associated with women.

Map of gendered names in the language-based

The more gender differentiation, the more indigenous the culture is.

The more advanced a society became, the more they moved towards a binary distinction between male and female.

Case-study: Slang for promiscuous men and women

(Sample from the Thesaurus of American Slang)

Men (Total 20): cad, cocksucker/(Aus.) cock teaser, gigolo,horndog, hornytoad, John, lech, mack, motherfucker (?), pimp,playboy, player, slut (?),stud, sugardaddy

Women: (Total 220): bimbo, bitch, chick, floozy, harlot, hooker, hussy,prostitute, skank, slag, slut, tart, tramp, trick, trollop, wench, whore/ho…

→ language-based stereotyping. A concept that is ok for men and not for women.

Animal Imagery: the chicken metaphor with no equivalent for men

The chicken metaphor tells the whole story of a girl’s life. In her youth she is a chick, then she marries and begins feeling cooped up, so she goes to hen parties where she cackles with her friends. Then she has her brood and begins to hen peck her husband. Finally she turns into an old biddy (Holmes, 2005:305)

Why avoid sexism in language?

Some people feel insulted by sexist language.

Sexist language creates an image of a society where women have lower social and economic status than men.

Using nonsexist language may change the way that users of English think about gender roles.

Gender differences in language use

Many stereotypes:

1. Men talk more than women.

2. Men are more likely to interrupt women than to interrupt other men.

3. There are approximately ten times as many sexual terms for males as for females in the English language.

4. During conversations, women spend more time gazing at their partner than men do.

In advertisements, there are variations of language use according to the targeted gender.

Gendered language variations theories

Two theories of gendered language variation

Two cultures model: different but overlapping speech communities (M/F)

Social power model: one speech community, with men setting the standard for “powerful” language (M>F)

The two cultures model

Men and Women are socialised into two different but overlapping cultural groups during same sex peer socialisation in childhood. These groups have different ideas about the purpose of language, as well as different understandings of pragmatic cues.

Girls and boys socialised separately in single sex peer groups, especially in formative years

Girls play in small groups or pairs; emphasis is on emotional closeness, not hierarchy. Emphasis on alliance formation, betrayal, loyalty.

Boys play in large groups with a range of ages. Emphasis is on hierarchy, on moving up in the hierarchy, in stealing attention away from people who are threatening your place in the hierarchy.

Different groups have different norms of interaction and goals for conversation. Miscommunication occurs across groups

When men and women talk to each other, it is a form of cross cultural miscommunication. Men’ and women’s goals for conversation may be very different due to different worldviews

Male/female worldviews in the Two cultures model

Male: Emphasis on social hierarchy, personal position within hierarchy, emphasis on individual accomplishments, independence

Female: Emphasis on social harmony, equality, concern for feelings of others, de-emphasis of self and self’s, accomplishments; emphasis on collaboration; avoidance of hierarchy

Examples

Women tend to use questions to maintain conversation, show interest and respect for the speaker’s story. / Men tend to see questions as requests for information, or even as challenges to their authority to speak.

Women share experiences to promote solidarity and intimacy / Men discuss problems in order to solve them.

Janet Holmes stated that women and men develop different patterns of language use.

Function: the purpose of the talk - Women tend to focus on the affective functions of an interaction more often than men do, while men are more interested in instrumental talk (instrumental function to find something out, to negotiate one's place in hierarchy…)

Solidarity: how the participants relate to each other - Women tend to use ling devices that stress solidarity more often than men do

Deborah Tannen coined the terms report talk (men) and rapport talk (women), and according to her men and women actually have totally different genderlects: a prescribed way of talking that is deemed to be normal for men or normal for women.

“Male and female conversation is cross cultural communication.”

Report talk: for men, conversation is about competition

communicate in order to gain status

exchange information

more likely to give advice and give orders that receiving them

seek conflict

Rapport talk: for women, conversation is about sharing and persuading

communicate in order to establish contact

exchange feelings, seek understanding and consensus

give proposals

Conversation is bonding

Women would imitate the language used by the person whom they talk to, while men would not change their use of language.

Maltz and Borker also worked on this hypothesis thanks to studies showing that language features were depending on intercultural dimensions.

The Social Power model

Robin Lakoff focused on why men and women in the US speak differently. To him, men use “powerful language”, while women use “powerless language”.

“men’s speech is powerful speech”

By this formulation, Lakoff means that men use speech typical of powerful people. By opposition, use speech typical of powerless people.

Examples of “powerless” speech:

hedge: gives options to the person whom they talk to (“Well, I was sorta thinking that maybe that we could kind of look at that tomorrow ish.”)

deference: “I know that you’re very busy , but I was hoping we could have some coffee, if you have the time”

self denigration: “This is probably a stupid idea, but what about if we each write one section of the report?”; “I really don’t know anything about this at all, but maybe people just don’t want to pay more for a dyson.”

marks of uncertainty: uncertainty: “um”; rising intonation at the end of a statement; hesitant or slow speech; quiet voice (women more concerned about the other person, it's the opposite for men)

Other features of women's Language

Vocabulary for fine color distinctions: mauve, beige, ecru, lavendar

Use of “meaningless” particles: like, ok, God, oh dear... (no semantic meaning, but supportive function in a conversation)

Use of certain adjectives: adorable, fabulous , sweet, lovely, divine

Use of tag questions: John is here, isn’t he

This is to be nuanced of course; his theory dates back to the 1970s'.

It seems that this power model is particularly relevant for politics, still today, as there are evidence and strategies showing the use of “power speech” as a more efficient use of language to convince and win/access power.

Kim Campbell (former prime minister of Canada; quoted in Eagly and Carli 2007, 102):

“I don’t have a traditionally female way of speaking … I’m quite assertive. If I didn’t speak the way I do, I wouldn’t have been seen as a leader. But my way of speaking may have grated on people who were not used to hearing it from a woman. It was the right way for a leader to speak, but it wasn’t the right way for a woman to speak. It goes against type.”

Dee Dee Myers (former Press Secretary for the Clinton administration; Quoted in Krum 2008):

“If male behavior is the norm, and women are always expected to act like men, we will never be as good at being men as men are.”

Marina Subirats (socióloga):

"Las mujeres, cuando queremos progresar, ser más libres, tendemos a imitar los comportamientos masculinos"

Case-study: Hillary Clinton’s campaign

Hillary Clinton is a great case-study as her language evolved through her political career, especially when she stood for the USA’s presidential elections.

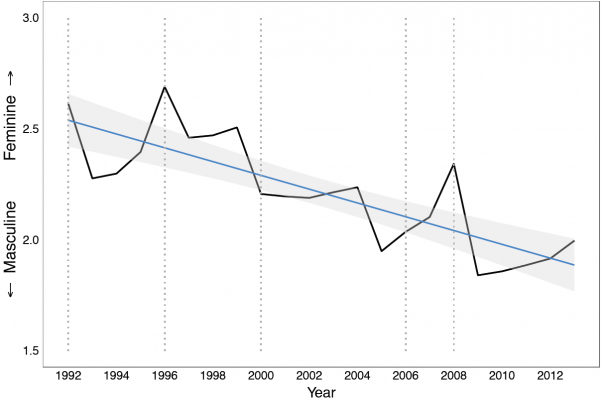

Masculine and feminine language were studied through various aspects, such as first person singular pronouns, anger, swear words, cognitive language and tentative wording.

Note: This graphic gives a yearly time series plot of the ratio of feminine to masculine linguistic markers. The dotted lines represent election years in which Clinton actively campaigned for herself (2000, 2006, 2008) or Bill (1992, 1996). The blue line represents a smoothed generalised linear estimate (with shaded confidence intervals) from the ratio model presented in table 2.

Hillary Clinton’s feminine language was particularly marked when she campaigned for her husband, in accordance with her role as “a supportive wife and first lady”. It progressively declined as she was either campaigning for a higher social/political position, or elected for this new and higher position.

“In essence, it is not clear that Clinton’s language was decreasingly feminine, but it is clear that her language was increasingly masculine. One need not come at the expense of the other.” (Jones 2016)

Register: from taboo language to overt prestige

Labov found that not only did language vary based on socioeconomic status, but women use more prestige features (status conscious), men more vernacular features (overt prestige).

“In stable sociolinguistic stratification, men use a higher frequency of nonstandard forms than women.”

“In change from above, women favour the incoming prestige forms more than men.”

“In change from below, women are most often the innovators.”

The most innovative use of language happens among women of an age from 15 to 18.

In studies of English, women have been found to speak a more prestigious variety than men in most communities. There might be the idea of a projection of themselves in the future as mothers, with the desire to pass on to children a variety that is perceived as of a higher economic class boundary.

Women’s speech [in English] has been found to be conservative where the dialect is moving away from the standard, and innovative where the dialect is moving toward the standard.

There’s now a softening of the expectations that women don't use swear words, but it is still common that they apologise for using them, while men would hardly ever apologise for that.

The new model: Performance

Performance theory focuses on community standards for judging the “genderedness” of linguistic behaviour in a given instance. Gets away from “men do this” “women do that” BUT acknowledges that there are power differentials in society that may be performed as part of performing gender identity.

Behaviour: Interruptions and overlap

According to Zimmerman and West (1975), men are more likely to interrupt women than they are to interrupt men: there’s a clear distinction between how men treat men and vice-versa.

Women do the “nonsense” work of conversation:

ask a lot of questions

use the pronouns “you” and “we” frequently

If women are interrupted, they tend to stop speaking

Say “yes,” “right” and “uhuh” frequently

Finishing each other's sentences is a mark of close relationships between women.

Men have more strategies for dominating conversation:

Interrupt frequently

Often don’t acknowledge or link their statement to a previous statement from an interlocutor

Make many declarations of fact

Often dispute claims of their interlocutor

Women listen more attentively than men in general.

Use and style of written language in an email

First: male (short, more concise, two questions in one forcing the answer of the first as an agreed point)

Second: female (longer, more developed, hedging, complete explanation, more opportunities for the receiver of the mail to answer no)

Other generalisations: men tend to shortcut the conversation, meanwhile women would let the conversation go on and on as they don't want to be the one finishing it.

The vocal fry

Acoustic characteristics:

dramatic swings from modal to breathy

relatively low pitch

produced with “head voice” phonation

Vocal fry: associated with young successful American women. It is seen as fake, stupid (negative perception)

More and more talk-up and vocal fry among Spanish and Irish teenagers

It is performed, it is not natural and one has to train to talk that way.

Linguistic correlates: use of Japanese Women's Language features: soft, sweet voice, used in public services.

Social correlates: Sweet voice characters tend to be supporting characters, not heroines (motherly, kind, mature, passive, conservative, traditionally beautiful)

What does a sweet voice tell us?

There are multiple ways of being feminine in Japanese popular culture.

There are strong perceived links between voice quality, language use, and personality characteristics.

The notion of the perfect woman who is a devoted wife and mother, which has old roots in Japan's history, is still alive and well.

Gossip

Gossip derives from Old English god sib ( = supportive friend or godparent)

Gossip is supposed to characterise much of women‘s talk, however men actually use more gossip than women.

Many people especially men think that gossiping means talking bad about others, however it is just any informal talk among close friends. It does not have a negative connotation like people (especially men) tend to believe. It is an easy and idle in-group talk in informal contexts. Its function is to affirm solidarity, to maintain social relationships.

Linguistic features of the gossip

Propositions which express feelings are often intensified.

Complete each other’s utterances, agree frequently, and provide supportive feedback.

Language and identity: Sexuality vs. Gender

Sexuality as a variable: does sexuality affect language variation?

Like gender, the “proximity” idea doesn’t quite work

Historical approaches

The study of language and its relation to homosexuality dates back as far as the 1920s, a time when homosexuality was considered pathological and/or criminal. It was decriminalised in Ireland in 1993.

Polari

A secret language (sociolect) used by gay men and women in the 1930s 1970s.

Examples:

Camp: effeminate,

Cottage: public toilet used for sex

dish: anus/bum

dolly: pretty

drag: clothing

naff: awful, tasteless

omi: man

omi-palone: gay man

palone: woman

Anti-language

Polari could be seen as a form of anti-language , a term created by Michael Halliday in 1978 to describe how stigmatised subcultures develop languages that help them to reconstruct reality according to their own values.

How is sexual orientation identity revealed in our speech?

Sounding gay and sounding lesbian

The sex/gender difference in transsexuals/transgendered persons

Can you tell the sexual orientation of someone without even seeing them?

“The Voice”

It is a cluster of phonetic features that have come to be associated with gay men’s speech, although not all gay men use “the voice” (some heterosexual men speak this way).

Some phonetic features of “the voice”

Wide pitch range

breathiness

lengthening of fricatives like /s/ and /z/

affrication of /t/ > [ts], /d/ > [dz]

Like feminine gendered women, feminine gendered gay men may use more adjectives and expressive words. In many places and in many languages, there are special sets of slang terms known by gay men.

Some say that gay men who use “the voice” want to identify themselves as different from the masculine heterosexual norm. On the contrary, lesbians may identify with rather than against straight women.

Features/Indexes of “Gay Language”

Gay men tend to use a wider pitch range compared to the speech of heterosexual men. (Goodwin 1989, Gaudio 1994)

They tend to use hypercorrect pronunciation so they’ll have phonologically non reduced forms. For example, saying fishing rather than fishin . (Walters 1981)

They tend to use hyper extended vowels (Barrett 1997)

Longer /s/ and /l/ sounds (Christ 1997)

They will also use a high to low intonational contour: fAABulous (Barret 1993)

use a number of features which were found to belong to Lakoff’s list of women’s language: empty adjectives and hedges. (Moran 1991)

“Sounding gay”

The idea that you can “sound gay” is based on to principles:

(1) Phonetic consonants, vowels, falsetto, creaky voice and nasality

(2) Social norms/expectations

Although a lesbian and gay approach calls for appreciating, or at least tolerating, sexual identity diversity, a queer approach problematises the very notion of sexual identities. Whereas a lesbian and gay approach challenges prejudicial attitudes (homophobia) and discriminatory actions (heterosexism) on the grounds that they violate human rights, a queer approach looks at how discursive acts and cultural practices manage to make heterosexuality, and only heterosexuality, seem normal or natural (heteronormativity).

(Nelson, 1999:376)

“Indexing”

Rather than claim that there is “gay language”, per se, another view is that speakers use language to “index” their identity or social status

Language can be used to index geography, socioeconomic class, ethnicity, gender or sexuality (Cameron & Kulick)

An important point: though we may talk about indexing as an active/conscious thing, it is much more likely to be unconscious;

Lavender Linguistics

Based on Queer Theory: the philosophical analytical viewpoint which questions all sexual and gender identity labels, whether biological or socially constructed (Butler, 2004, p. 7)

1. In contrast to common ideologies about “the voice,” there are multiple ways of presenting a gay identity

2. In contrast to the interpretation of “one variable, one meaning” a variable can index a field of meanings and multiple identities

References

Baker, Paul (2008). Sexed Texts: Language, Gender and Sexuality. London: Equinox. (This book offers a review of the literature on language and gender and a main focus on linguistic performance and its role in the construction of gender and sexuality for identities and ideologies.)

Braun, F. (1997) ‘Making men out of people: the MAN principle in translating genderless forms’, pp. 3–30, in Kotthoff, H. and Wodak, R. eds. Communicating Gender in Context, Amsterdam CrossRef | Google Scholar, John Benjamins.

Bing, J. and Bergvall, J. (1996) ‘The question of questions: beyond binary thinking’, pp. 1–30, in Bergvall, V., Bing, J. and Freed, A. eds. Rethinking Language and Gender Research: Theory and Practice, London Google Scholar, Longman.

Bourdieu, P. (1991) Language and Symbolic Power, Cambridge Google Scholar, Polity Press.

Bradby, B. (1990) ‘Do-talk and don't talk: the division of subject in girl-group music’, pp. 341–68, in Frith, S. and Goodwin, S. eds. On Record: A Rock and Pop Reader, London Google Scholar, Routledge.

Cameron, Deborah and Don Kulick (2003) Language and Sexuality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cameron, Deborah (2009). Sex/Gender, Language and the New Biologism. Applied Linguistics 31(2): 173 92. (This article examines and refutes arguments that differences between male and female speech are based on biological differences.

Campbell, Karlyn Kohrs. 1998. “The Discursive Performance of Femininity: Hating Hillary.” Rhetoric & Public Affairs 1(1): 1–20.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Carlin, Diana B. and Winfrey, Kelly L.. 2009. “Have You Come a Long Way, Baby? Hillary Clinton, Sarah Palin, and Sexism in 2008 Campaign Coverage.” Communication Studies 60(4): 326–43.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Carroll, Susan J. 2009. “Reflections on Gender and Hillary Clinton’s Presidential Campaign: The Good, the Bad, and the Misogynic.” Politics & Gender 5(1): 1–20.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Coates, Jennifer (1986) Women, Men and Language. London:Longman.

Eagly, Alice H. and Carli, Linda L.. 2007. Through the Labyrinth: The Truth about How Women Become Leaders. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.Google Scholar

Eckert, Penelope. 2000. Linguistic Variation as Social Practice. Oxford: Blackwell.Google Scholar

Foley, William A. (2012) Anthropological Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405198431.wbeal0031

Gaudio, Rudolph (1994) “Sounding Gay: Pitch Properties in the Speech of Gay and Straight Men.” American Speech 69:30-57.

Harrington, Kate, Lia Litosseliti, Helen Sauntson, and Jane Sunderland (eds.) (2008). Gender and Language Research Methodologies. London: Palgrave Macmillan. (This book presents introductions to a variety of approaches to studying gender and language, including interactional sociolinguistics, CA, corpus linguistics, CDA, discursive psychology, feminist post structuralist.)

Holmes J (1988) Of course: A pragmatic particle in New Zealand women’s and men’s speech. Australian Journal of Linguistics; 2, 49–74.

Holmes J (1990) Hedges and boosters in women’s and men’s speech. Language and Communication; 10 (3): 185–205.

Irvine, J. (1974). Strategies of status manipulation in the Wolof greeting. In R. Bauman & J. Sherzer (Eds.), Explorations in the ethnography of speaking (pp. 167–91). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Jones, J. J. (2016). Talk “Like a Man”: The Linguistic Styles of Hillary Clinton, 1992–2013. Perspectives on Politics, 14(3), 625–642. doi:10.1017/S1537592716001092. Available: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/perspectives-on-politics/article/talk-like-a-man-the-linguistic-styles-of-hillary-clinton-19922013/0F8189E4F3221D78C6233C2F38C72A3E

Jones J. J. (2016) Hillary Clinton talks more than a man than she used to. The Washington Post. Available: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2016/08/19/hillary-clinton-talks-more-like-a-man-than-she-used-to/

Krum, Sharon. 2008. “Why Women Really Should Rule.” The Guardian, March 26. http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2008/mar/26/women.gender, accessed October 2015.Google Scholar

Labov, William (1972) Sociolinguistic Patterns. Philadelphia:University of Pennsylvania Press.

Lakoff, Robin (1972) Language and Woman’s Place. New York:Harper & Row.

MacKenzie, A., McGuire, D. and Kissack, H. (2017) “The use of gendered language in speeches made by Trump and Clinton adhered to stereotypes of the roles of male and female leaders.” The London School of Economics and Political Science. Available: http://bit.ly/2r4ANcP

Moonwomon Baird, Birch (1997) “Toward a Study of Lesbian Speech.” In Anna Livia and Kira Hall (eds.) Queerly Phrased: Language, Gender and Sexuality. New York: Oxford University Press.

Motschenbacher, Heiko (2011). Taking Queer Linguistics Further: Sociolinguistics and Critical Heteronormativity Research. International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 212 :149-79 (This article addresses criticism against Queer Linguistics as a post structuralist approach and makes suggestions for methodologies to empirically study language and sexuality.)

Mulac, A., Bradac, J. J., & Gibbons, P. (2001). “Empirical support for the gender-as-culture hypothesis: An intercultural analysis of male/female language differences”. In Human Communication Research, 27(1), 121–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2001.tb00778.x

Murphy, Lynn (1997) “The Elusive Bisexual.” In Anna Livia and Kira Hall (eds.) Queerly Phrased: Language, Gender and Sexuality. New York: Oxford University Press.

O’Barr, William and Bowman Atkins (1980) “‘Women’s Language’ or ‘Powerless Language’?” In Sally McConnell Ginet, Ruth Border and Nelly Furman (eds.) Women and Language in Literature and Society. New York.

Sorrentino, J., Augoustinos, M., & LeCouteur, A. (2022). “Deal me in”: Hillary Clinton and gender in the 2016 US presidential election. Feminism & Psychology, 32(1), 23-43. https://doi.org/10.1177/09593535211030746

Stanley, Julia P. (1970) “Homosexual Slang.” American Speech 45:45-59.

Tannen, D. (1990) Gender differences in conversational coherence: Physical alignment and topical cohesion. In B. Dorval (Ed.), Conversational organization and its development (pp. 167–206). Ablex Publishing.

Tannen, D. (1991) You just don't understand. Women and men in conversation. Review available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/46314186_Tannen_D_1991_You_just_don't_understand_Women_and_men_in_conversation

Tranchese A and Zollo SA (2013) The construction of gender-based violence in the british printed and broadcast media. Critical Approaches to Discourse Analysis across Disciplines; 7 (1): 141–163.

Trudgill, P. (2000) Sociolinguistics: An Introduction to Language and Society, 4th edition. London: Penguin Books.

El rincón de lectura

Para saber más acerca de las lenguas y otros temas vinculados

Un poco de lectura ligera sobre temas lingüísticos, literarios o sociales, ¡venga a echarles un vistazo!

Teorías y reflexiones sobre la traducción

Your perfect tech rider

Sociolingüística: conceptos claves

Language accessibility in live performances

Aprender una nueva lengua

Oportunidades de vivo para artistas emergentes

Fracasos de traducción

Subtitling: use(s) and norms

La localización

Tablón de ofertas laborales en la industria musical

El inglés en Irlanda

Youth Language

Onomatopeyas a través del mundo

La manipulación de las palabras y realidades en la política

El lenguaje tabú

Language attrition

Cuando la comedia se burla de la interpretación

The meme corner - La música

The meme corner - Ser un(a) traductor(a) / intérprete

The meme corner - La lingüística

The meme corner - La traducción

The meme corner - La comida en el mundo