Le langage tabou

Introduction: qu'est-ce que le langage tabou ?

Le tabou est « une proscription de comportement pour une communauté spécifique d’une ou plusieurs personnes à un moment spécifiable dans des contextes spécifiables ». (Keith Allan - Oxford Handbook of Taboo Words and Language)

« Ce qui est en fait rendu tabou est l’utilisation de ces mots et ce langage dans certains contextes ; en bref, le tabou s’applique à des cas de comportement de langage. Pour que le comportement soit proscrit, il doit être perçu comme nuisible d’une façon ou d’une autre pour un individu ou sa communauté mais le degré de nuisance peut se situer n’importe où sur l’échelle, d’une transgression de la bienséance à la mort. Tous les comportements tabous sont dénigrés et ils provoquent une sanction sociale voire légale. Les tabous sont décrits et les raisons et croyances derrière sont étudiées. Les mots tabous sont typiquement neutralisés par remplacement, par exemple dans le cas des insultes et des jurons : le langage tabou est évité à travers divers types d’euphémisme. »

Historiquement, l’usager type du langage tabou (fort) est un homme de moins de 35 ans, ouvrier non qualifié/travailleur manuel/sans emploi.

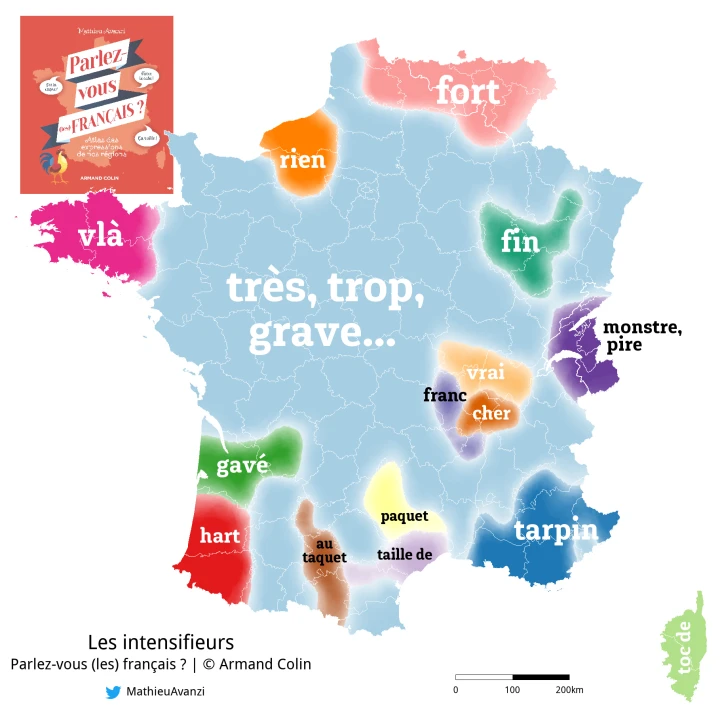

L'argot

Selon le dictionnaire de l'Académie Française, l’argot est « le vocabulaire qu'adoptent entre eux les gens d'une même profession, d'un même milieu. ». L’argot est un langage très familier. Il peut offenser les gens s’il est utilisé à propos de personnes extérieures à un groupe qui se connaît bien. On utilise habituellement l’argot à l’oral plutôt qu’à l’écrit. L’argot se réfère normalement à des mots et sens spécifiques, mais il peut inclure des expressions (idiomatiques) plus longues.

(Pour ceux et celles qui apprennent le français, une vidéo similaire est disponible ici - n'hésitez pas à consulter les autres vidéos de cette excellente professeure : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c28nUMy68H0)

Les gros mots

Il existe encore peu d’études sur l’utilisation des jurons, ou « gros mots », en France.

Un premier exemple intéressant, à approfondir toutefois, est celui de l’enquête réalisée par Preply en métropole : « Les villes françaises qui jurent le plus ».

En France, les jurons les plus utilisés sur le net en 2024 sont, du plus ou moins utilisé : gueule (23,400,000 résultats), con (84,500,000 résultats), salope (9,450,000 résultats), merde (7,870,000 résultats), putain (6,180,000 résultats), bordel (6,070,000 résultats), niquer (4,510,000 résultats), couilles (4,310,000 résultats), chier (3,830,000 résultats), enfoiré (2,400,000 résultats), conne (1,710,000 résultats), bâtard (1,240,000 résultats), salaud (935,000 résultats), connard (790,000 résultats), branleur (534,000 résultats), enculé (529,000 résultats), connasse (333,000 résultats), bâtarde (119,000 résultats), enfoirée (3,580 résultats), branleuse (1,550 résultats), enculée (1,120 résultats).

A noter que l’usage est davantage oral, et plutôt dans un cadre privé que public, bien de plus en plus présent dans les médias voire même dans la politique. Les résultats de la recherche Internet ne sont donc pas à considérer comme indicatifs de la réelle utilisation de ces mots par les Français. Ils peuvent également inclure des termes utilisés de manière non péjorative dans un contexte donné, souvent avec la signification originelle du mot, comme « bâtard » pour désigner un animal n’appartenant pas à une race, ou pour des titres d’œuvres comme le film « Connasse, Princesse des cœurs » d’Eloïse Lang et Noémie Saglio.

On remarque en revanche déjà une disparité entre les variantes masculines et féminines de certaines insultes.

Une liste plus détaillée est disponible dans l’article de Sacha Aulagnier.

Quelques jurons expliqués :

L’utilisation des gros mots dans différents groupes sociaux

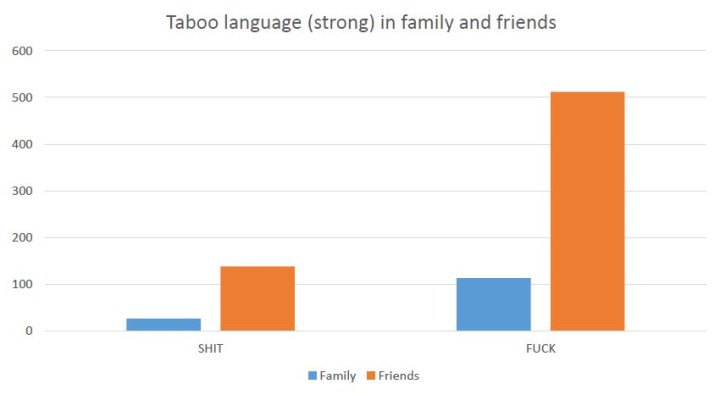

Stenström et al. (2002, p.77) met en relation le langage tabou (gros mots principalement) avec l’affinité au groupe : « plus l’affinité au groupe élevée, plus il y a de jurons ». Les éléments tabous ont une fonction sociale en tant que « signaux d’intimité » qui ont pour but de créer un environnement familier et amical (Stenström 1991).

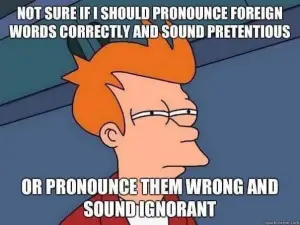

→ Observez les stéréotypes culturels en regardant les schémas d’utilisation du langage ;

→ Évitez les généralisations qui ne sont pas basées sur des preuves et remettez en question celles qui le sont.

Les attitudes envers l’utilisation du langage tabou

Using taboo language, particularly swearing / profanity, has historically been pejorative, but this can be nuanced especially today, depending on the context and intentions behind this use. It can be a tool for covert prestige, in an attempt to have a positive image and even integrate in a specific social group. It seems this practice has been increasing in the last few years, especially in politics, where surveys show that candidates can be more convincing and successful when swearing publicly.

The gender gap in taboo language use and attitudes

'In many speech communities across all social groups, women are thought to be more status-conscious than men are and generally use more formal, standard forms of speech. A number of sociolinguistic studies have suggested that women, irrespective of social characteristics such as class, or age, use more polite standard forms of language than their male counterparts.' (Romaine, 2000)

‘Women shouldn't say bad words. RT if you agree.’

This statement was published by American podcaster Nicholas J. Fuentes on his Twitter account. Far from being an isolated opinion, the idea that women should not swear, or as it is often expressed in mainstream culture and social media, that swearing is not “lady-like”, has long been heard and transmitted in society. Indeed, even though swear words are often taboo or seen negatively, it seems that the attitude towards them differs according to who uses them.The distinction is particularly relevant when applied to genders: women are judged and refrained in their use of swear words by the influence of this collective judgement, a phenomenon that has caused – and to some extent has been caused by – a lower use of swear words than that of men.

The study of taboo language use and attitude according to the gender is part of the broad subject of gender language. A good base to understand it is Language and Gender by Ecquert and McConnell-Ginet (2003). Quoting Butler (1990), they aptly state that gender is “something we perform” (p.10). From this perspective, the intentional use of swear words, whether by men or women, might be considered as a gender performance, as it follows gendered language behaviours and provokes different attitudes according to the speaker's gender. Ecquert and McConnell-Ginet's reflection about the early origins of this performance also highlights the early acquisition and assimilation of the use of swear words and related attitude according to gender. Indeed, teaching children a certain use of the language (and related values) and talking to them differently based on those children's gender will make the children talk accordingly and judge others, transmitting what their parents – and by extension society – have taught them. Western society has in this context developed specific linguistic stereotyping applied to gender: women “do not swear”, it is not “lady-like”, they have “emotional language” while men have “strong language”...

‘Some researchers (e.g., De Klerk, 1992), regard women still stereotypically as guardians of the language and seen to be more ladylike and avoid dirty words in particular. Society’s social and cultural expectations vary regarding male and female taboo usage. Taboo has traditionally been regarded as aggressive and forceful and thus, it belongs to the language domain of males rather than females. Women’s speech, on the other hand, has generally been perceived as being polite, pure and sterile. Women’s subordinate social status in society is reflected in the taboo language women use. The idea that women should be lady like in their speech and their behavior can be seen as functioning as a form of social control. ‘ Susan E. Hughes (1992)

Case Study: gender differences in use and attitudes in France, Ireland and Latam

When conducting a survey (2020) on participants from different French, Spanish and English speaking countries, I found that despite their cultural distinctions, and thus different language use and judgements, those three groups share common ideas about the use of swear words by women.

Firstly, what is brought out of the results is a general confirmation of the theory that women use less swear words than men, or at least less often (a tendency that tends towards the contrary for Frenchpeople). While women declare using them almost as much as the men, the details of the swear words used and their frequency lessens this statement. The estimation of women's use of swear words is generally above the actual use: although they believe it is said by all and should be said by all (idea generally shared by men, at least in this first general question), they seem to still restrain from saying them themselves, or to have been brought up without this part of language practice, making a clear distinction between belief and actual language practice.

It also seems that people preferably use swear words that they consider not very strong, or avoid those they consider very strong. It is almost always the case with women, but the contrary might be observed for men: this could be related to an act of identity, a gender performance (the use of swear words being often associated to men, those who identify to this gender or want to be particularly recognised as 'standard' men according to this ideology then perform or over-perform this characteristic). Women also generally assign more strength to swear words than men, even in the case of the French who use them more despite this assigned strength.

The contextual use of swear words determines a part of gender relationships: it is clear from the survey results that both men and women change or regulate their use of swear words according to the gender of those they are speaking to. There is a tendency in both cases to use more swear words when talking to men, it is particularly true for men (rather use swear words when in groups of men). This could be related to the Communication Accommodation Theory (Giles and Ogay 2007), as a way to adapt to the idiolect of the interlocutor, or to the idea that both genders perform a certain speech according to how they should interact with the same or opposite gender (their language ideology) and not to the exact specificities of the actual person they are talking to.

For Breckler (1985, p.203), the cognitive and affective aspects of attitude do not necessarily induce the behavioural aspect, the three being only moderately correlated. Thus, the results of the survey concerning the advice or direct criticism by men to women when using swear words cannot express a clear link between (negative) attitude towards this use and related “overt actions”. A low proportion of participants (from a quarter to a third) declared they had already advised or criticised the use of swear words by women, but this result doesn't indicate if when hearing or reading them the others participants were annoyed or had any other type of negative affective attitude (the advice might be done without personal negative feeling, as a simple transmission of the ideology, or the absence of behaviour might hide a non-expressed negative feeling...).

The acceptability for the use of some swear words according to gender is linked to the strength of the word (women being usually supposed to use less strong words or to use 'softer' swear words) or to the fact that some words are particularly insulting for one or the other gender. This shows a gendered value of those swear words, which can be explained by the generally patriarchal stance of language in society (in the communities studied through the survey). An example of the unbalanced gendered swear words is the existence of 220 words to qualify a promiscuous woman (used by extension to all women when the speaker aims to insult them) as opposed to the 20 words used to qualify a promiscuous man (Chapman 1989). Eltahawy (2019, p.77) argues in this context that “we need more non-gendered swear words”.

The data confirms Holmes' theory (2008, p. 405) that attitude to the language is shifted towards attitude to the speaker (a woman using swear words would then herself be 'from a lower class', 'not educated', 'not intelligent'... Although those answers are not in the majority). The link drawn in the data between swearing and social class or education might be connected to the fact that women tend to use more prestige features (Labov 1966) and to prefer standard varieties (Ecquert and McConnell-Ginet 2003, pp 292-304). Another link could be drawn between the resulting expectation for women to speak with standard prestigious variety and the negative attitude created when women use swear words that go against those prestige features. As seen with Breckler (1985), this generally negative attitude expresses itself through statements of opinion (affect) or presumed knowledge (cognition) as collected in the survey, and also in some cases through concrete actions (behaviour) when the participants affirm having advised women to avoid swearing or criticised them for this practice, and in the case of women having already been criticised or restrained their normal use of swear words. The behavioural aspect of the attitude reveals a new perspective when considering women's use of swear words: it is influenced, and to some extent controlled – or auto-controlled – by social values sometimes embodied by those who try to repress what they think is wrong (here advising, criticising or even insulting like on Twitter). Whether consciously or subconsciously, directly or indirectly, addressed at a very young age or later, this phenomenon has an impact on women’s language. Eltahawy (2019, p.77) relates this control by the “patriarchy” to its control of the woman's body.

Overall, women saying less swear words than men appears as a common fact in the data, though not to the same extent (the distinction is much lower for the French). People choose their words according to their perception of the word's strength (which is sometimes favoured by men and mostly avoided by women) and according to the context or the people whom they are talking to. Many of the participants wrongly consider that women who use swear words are from lower social classes or less intelligent (the two criteria being often correlated in the answers: this social perception might be studied more deeply in further research, using matched guise technique for example). Although the number of participants is relatively low for a research of this kind, and restricted in terms of variations in age and gender, it can serve as a good base to develop further studies on the subject. In this type of data collection, one does not control the exactitude and honesty of the answers, and is thus forced to take for granted that they are reliable. This can be a factor to take into account in the validation of the study's results.

References

Allan, Keith (ed.) (2018) The Oxford Handbook of Taboo Words and Language, Oxford Handbooks (online edn, Oxford Academic). Available: https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198808190.001.0001

Arbury, J. (1996) Discover New Zealand. English for speakers of other languages. Auckland: J. Arbury.

Bailey, L. &Timm, L. (1976) More on women and men’s expletives. Anthropological Linguistics, 18(9), 438-449.

Baker, C. (1992) Attitudes and language, Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Bayard, D. &Krishnayya, S. (2001) Gender, expletive use, and context: Male and female expletive use in structured and unstructured conversation among New Zealand university students. Women and Language, 26(1), 1-15.

Blum-Kulka, S., House, J., & Kasper, G. (1989) Cross cultural pragmatics: Requests and apologies. Norwood, New Jersey: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Breckler S. (1985) 'Empirical validation of affect, behavior, and cognition as distinct components of attitude'. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 1191-1205, available: DOI: 10.1037//0022-3514.47.6.1191. [accessed 03 May 2020]

Bucholtz, J., Liang, L.C.,& Sutton, L. A. (1999) Reinventing identities: The gendered self in discourse. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Carter, R. (1997) Investigating English discourse. Language, literacy, and literature. London: Routledge.

Carter, R. & McCarthy, M. (2001) Size isn’t everything: Spoken English, corpus, and the classroom. TESOL Quarterly, 35(2), 337-340.

Chapman R. L. (1989) Thesaurus of American slang, London: Collins.

Coates, J. & Cameron, D. (1988) Women in their speech communities: New perspectives on language and sex. London: Longman.

Coates, J. (1986). Women, men and language: A sociolingusitic account of sex differences in language. London: Longman.Google Scholar

Conklin, N.F. (1973). Perspectives on the dialects of women. Paper presented at a meeting of the American Dialect Society.Google Scholar

Culpeper, Jonathan. (2018) Taboo language and impoliteness. 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198808190.013.2. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331179684_Taboo_language_and_impoliteness

De Klerk, V. (1992) How taboo are taboo words for girls? Language in Society, 21(2), 277-289.

Dumas, B. & Lighter, J. (1978) Is slang a word for linguists? American Speech, 53(1), 5-17.

Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Research, 2019, 6(1) 83

Ecquert P. and McConnell-Ginet S. (2003) Language and Gender, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Eltahawy M. (2019) The Seven Necessary Sins for Women and Girls, UK: Beacon Press.

Fine, M. & Johnson, F.L. (1984) Female and male motives for using obscenity. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 3(1), 59-74.

Giles, H., & Ogay, T. (2007) 'Communication Accommodation Theory', In Whaley, B. B. and & Samter, W. (Eds.), Explaining communication: Contemporary theories and exemplars (pp 293-310), NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Holmes, J. (2008) An introduction to sociolinguistics. Third edition. Harlow:Longman.

Holmes, J. (2001) An introduction to sociolinguistics. (2nd ed.). London: Pearson Education.

Hughes, D. (1992) Expletives of lower working-class women. Language In Society, 21(2), 291-303.

Indy100. (2023) “Every British swear word has been officially ranked in order of offensiveness”. Available: https://www.indy100.com/viral/british-swear-word-ranked-offensiveness-2659905092

Jafari Baravati, A. and Rangriz, S. (2019) Taboo Language and Norms in Sociolinguistics. Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Research, 6(1), 75-83. Available online at www.jallr.com. ISSN: 2376-760X

Jespersen, O. (1922) Language: Its nature, development and origin. London: Allen &Unwin.

Johnson, J. (1993) A descriptive study of gender differences in proscribed language behavior, beliefs, and attitudes. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the National Council of Teachers of English. Pittsburgh, America.

Johnson, S. (1996) English as a second F*cking language. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Kasper, G. (1990) Linguistic politeness. Current research issues. Journal o fPragmatics, 14, 193-218.

Kocoglu, Z. (1996) Gender differences in the use of expletives: A Turkish case. Women and Language, 19(2), 30-35.

Kramsch, C. (1998) Language and culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Labov, W. (1966) The Social Stratification of English in New York City, Washington: Center for Applied Linguistics.

Lakoff, R. (1975) Language and woman’s place. New York: Harper Collins.

Limbrick, P. (1991) A study of male and female expletive use in single and mixed-sex situations. Te Reo. Journal of the Linguistic Society of New Zealand, 34, 71-89.

McCarthy, M. & Carter, R. (2001) Size isn’t everything: Spoken English, corpus and the classroom. TESOL Quarterly, 35, 337-340.

Oliver, M, & Rubin, J. (1975) More on women’s and men’s expletives. Anthropological Linguistics, 18(9), 438-449.

P, D. (2023) “All Australian Swear Words Ranked In Survey – Minimally Offensive to Brutal”. Australia Unwrapped.com. Available: https://www.australiaunwrapped.com/all-australian-swear-words-ranked/

Risch, B. (1987) Women’s derogatory terms for men: That’s right, “Dirty” words. Language in Society, 16(3), 353-358.

Romaine, S. (2000) Language in Society. An introduction to sociolinguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ross, J. (2003) Bleep! A guide to popular American obscenities. (2nd ed.). America: Octavo Books.

Rumsey, A. (1990) 'Wording, meaning and linguistic ideology." American anthropologist, 92(l), 346-3, available: https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1990.92.2.02a00060 [accessed 04 May 2020]

Selnow, G. (1985) Sex differences in uses and perceptions of profanity. Sex Roles, 12(3&4), 303-312.

Stapleton, K. (2003) Gender and swearing: A community practice. Women and Language, 26(2), 22-33.

Thomas, L. &Wareing, S. (1999) Language, society and power. An introduction. London: Routledge.

Trudgill, P. (1983) Sociolinguistics: An introduction to language and society. London: Pelican.

Trudgill, P. (2000) Sociolinguistics. An introduction to language and society. (4thed.). London: Penguin Books.

Vilalta, L. B. (2001) There are no more angels: Non-swearing women are a myth. Tarragona: UniversitatRovira I Virgili.

Wardhaugh, R. (1998) An introduction to sociolinguistics. (3rd ed.). Oxford: Basic Blackwell.

West, C. &. Zimmerman, D. (1983) Small insults: A study of interruptions in cross-sex conversations between unacquainted persons. In Thorne, B., Kramarae, C. and N.Henley (Eds.), Language, gender and society. 103-117. Rowley: Newbury House.

Wierzbicka, A. (1990) Cross-cultural pragmatics and different values. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, 13(1), 43-76.

Wordtips blog (2023) The United States of Cussing: Every U.S. State's Favorite Swear Word. Available: https://word.tips/us-states-curse-words-map/

Twitter Posts (per usernames)

Asa'ah, S. (@AsaahSamuel) (2020) Want some Burgundy to lubricate the swearing, lady? [Twitter], 10 Apr 2020, 11:32 pm, available: https://twitter.com/asaahsamuel/status/1248725544428023815 [accessed 04 May 2020]

Debrah, A. (@Ameyaw112) (2018) Ladies should not swear [Twitter], 23 Aug 2018, 10:22 am, available: https://twitter.com/ameyaw112/status/1032543525349543937 [accessed 04 May 2020]

Filer, D. (@DannyFiler) (2019) Also side note, and maybe it's the cynicism of kicking in, but I really don't believe this working class swearing lady would've got this job in no.10. [Twitter], 24 Dec 2019, 3:12 am, available: https://twitter.com/DannyFiler/status/1209295667115507712 [accessed 04 May 2020]

Fuente, N. J. (@NickJFuentes) (2018) Women shouldn't say bad words. RT if you agree. [Twitter], 12 July 2018, 10:10 pm, not available anymore.

Hayes, D. J. (@DavidJHayes2) (2020) It's an adversarial process. It doesnt work if the press and political sphere are in love. As for abuse. Well I could post some headlines aimed at the president from these virtuous journos. But I'm too polite to engage in mud slinging. Watch your language. You're a lady. [Twitter], 26 Apr 2020, 2:11 pm, available: https://twitter.com/DavidJHayes2/status/1254382550568570887 [accessed 04 May 2020]

Unknown (@Iwanta_coffee) (2020) One thing that is coming across from the tweets is that these feminists are just plain rude and aggressive. Instead of saying "thanks but no thanks" they resort to swearing (not very lady like) and being obnoxious [Twitter], 10 Mar 2020, 8:37 pm, available: https://twitter.com/I_want_a_coffee/status/1237462636159262721 [accessed 04 May 2020]

Unknown (@lady12) (2020) Do you know what #COVID19 has taught me? It has taught me to swear. My mom raised me that swearing isn’t lady like.For the first 41 years of my life I’ve taken that seriously. I say things like ‘frick’ or’eff that’ but I decided to not swear. Things change. And FUCK YOU #COVID19! [Twitter], 29 April 2020, 7:01 am, available: https://twitter.com/_Lady12/status/1255361469375483904 [accessed 04 May 2020]

Seven, K. (@KassandraSeven) (2019) That reminds me of a story: My mother caught me swearing when I was about 9 years old. She sternly informed me: “Ladies do NOT cuss!” I told her: “well then I don’t wanna be a Lady.” The end. [Twitter], 6 Jan 2019, 1:51 am, available: https://twitter.com/KassandraSeven/status/1081714903587741697 [accessed 04 May 2020]

Turner, E. (@EileenTurner8) (2020) Don't know about naming the dog but I can think of a few (that I won't say because I'm a lady and don't like swearing) for the people that did this to the poor animal. [Twitter], 8 Feb 2020, 10:24 am, available: https://twitter.com/EileenTurner8/status/1226074297686466560 [accessed 04 May 2020]

Vengerberg, J. (@BeautyYennifer) (2020) [ Yennefer was a woman not of airs and graces but she was more a woman who said it how it was. She stood up to any man or woman. Her tongue could be quite acid at times often putting others in their place. Her swearing too could be quite unladylike. Although she looked like > [Twitter], 25 Apr 2020, 9:43 pm, available: https://twitter.com/BeautyYennifer/status/1254133921362710529 [accessed 04 May 2020]

Le coin lecture

Pour en savoir plus sur les langues (et sujets dérivés)

Quelques articles sur des sujets linguistiques, littéraires ou sociaux, venez jeter un œil !

Translation theories and thoughts

Votre fiche technique parfaite

Sociolinguistics: key concepts

Language accessibility in live performances

Apprendre une nouvelle langue

Live opportunities for emerging artists

Les ratés de la traduction

Le sous-titrage : utilité(s) et normes

Localisation

Music Industry Jobs Boards

English in Ireland: Irish English

Youth Language

Onomatopeias across the world

Language and gender

Manipulating words and reality in politics

L'attrition langagière

Quand la comédie parodie l'interprétation

The meme corner - Music

The meme corner - Being a translator/interpreter

The meme corner - Linguistics

The meme corner - Translation

The meme corner - Food around the world